“There were many interesting experiences associated with the newspaper job. One time we went up to Philipp to cover a story where a man had fallen into a huge tank of beans and only his head was sticking out. They were afraid he would suffocate, and firemen and others worked for hours before they finally rescued him that night. We stayed until they got him out.

“There were many interesting experiences associated with the newspaper job. One time we went up to Philipp to cover a story where a man had fallen into a huge tank of beans and only his head was sticking out. They were afraid he would suffocate, and firemen and others worked for hours before they finally rescued him that night. We stayed until they got him out.

“I had to work sometimes twelve or fourteen hours a day when we had catastrophes like the flood in 1973 and the tornadoes in 1971. Those were the times when I was exhausted, but they were also the most exciting times to be a reporter. It was the society, the sports and the obits that became so boring.

“We had taken Cathy back to Ole Miss in February, 1971. It was a Sunday afternoon, and I was hating to see her go because she had a flu-like illness. The clouds had been boiling and the pavement sweating all day. Just before we left to go to Oxford, Ed McCafferty, the Civil Defense direcctor, called me and told me that there were storm warnings out all over the state. He had never called to tell me this before even though I always checked with his office when we were under a watch or warning. Just as we approached Greenwood coming home the sky became almost black and it was obvious we were getting ready to have bad weather.

“We had just walked in the house when Elmer Gwin next door called and said he had heard that Inverness had been almost blown away. Since Inverness was not far from here we really began to worry. I had just told Russell I thought we might be smart to get under a table or something when we decided to go to the Court House where the Civil Defense office was located in the basement. When we arrived there the Court House was full of people who had left their homes to come there because the basement had been designated as a shelter. It was utter bedlam and calls were coming in from all over the county saying tornadoes had struck and people were killed and hurt. A highway patrolman and his wife from Grenada had been blown off the road in their car at Fort Pemberton and killed. The storms had struck just west of Greenwood and throughout the whole county.

“I was trying to get information to call in to the paper and could not get through to the hospital to see how many injured had been brought in, so Russell suggested I go with two fellows who worked for the radio station to the hospital to get information while he would stay at the Court House. They had a small Volkswagen, and I had never seen either one of them before, but we headed out together. We had had torrential rains, and River Road was under water.

“I could see other cars stalled and kept telling them they should not head down there in that little car, but they ignored my warnings and went right ahead. Mr. Gillette and his son, both crazy, who lived on River Road were standing in the water waving to cars to turn back. By this time we were stalled in water which was up to the floorboard, and Mr. Gillette was beating on the car and cursing and telling us to go back. I didn’t know whether I was going to drown or be killed by a crazy man. Anyway, I decided it was time to abandon the car and head back to the Court House about a block away. All the time the men were telling me that if I opened the car door the water would ruin their camera equipment, but at this stage I didn’t care. I got out, held my dress up, and waded through the water which was over my knees. Some of the neighbors shouted for me to come on over to their house, which I did and called the police and told them to come calm the Gillettes down.

“I walked on over to the Court House barefooted and holding my ruined shoes in my hand. Russell said he was glad I had at least taken my girdle and stockings off when we got home from Oxford. Anyway, I worked the rest of the night barefooted and with a wet dress. In fact, when Russell and I finally got to the hospital by another route. I walked in in that shape and I think they thought I was one of the victims.

“It was a hairy night to say the least. Thirty-nine people in the county were killed and hundreds injured and dozens of houses in the rural areas destroyed.”

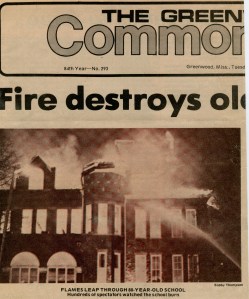

Teletype copy for a tornado-related storyLetter of thanks to Sara from Senator James Eastland

So many of Sara’s escapades run together in my mind now: Fires, civic unrest, political rallies, board meetings, it’s hard to differentiate one particular event from another. But the night of the tornadoes in February, 1971, stands out clearly. I was under the kitchen table when Sara and Russell returned from Oxford, and I remember clearly voicing my concern over their sanity when they said we were heading across town to the Court House. It was one of those late afternoons when the sky was a color not normally found in nature and the concrete was puddling with sweat. You knew something very, very bad was coming over the horizon, but radio and TV weather coverage was so limited then that it would be almost on you before you knew it. My vote to stay home was overruled and we bundled into the car for the trip across the Yazoo. Russell drove, Sara scribbled notes to herself and I got down on the back floorboard. As we came across the new bridge, I looked west out the back seat window and saw the funnel cloud lifting up over the river out by the hospital and the Buckeye. It was becoming quite apparent that this was not going to be one of Sara’s adventures that was in and out and over quickly. We were in for a long night.

The Civil Defense department in the basement of the Court House was familiar territory to me. In those days of the Cold War, it was the storage site for huge cans of beans and cases of Spam, our disturbing culinary fate if the Russians dropped the Big One on us (which, of course, we were sure they were planning, given the crucial strategic importance of Leflore County, with its vital grain elevators and access across three rivers). On a normal day, the CD rooms were quiet and fun to explore, but on that winter night there was barely controlled chaos. Reports were filtering in that several small Leflore County plantation communities had all but disappeared and no one seemed to know how many were dead or injured. I remember Sara heading out for the hospital, but I don’t recall whether I wanted to go with her. It would have been better if I had, as I could at least swim; she never learned. What I do remember is her return to the Court House, looking for all the world like a sheepdog that had been caught in the pasture during a thunderstorm. Russell was sympathetic but trying to hold back his laughter, and she didn’t appreciate that one bit.

We made it through that night, and many folks didn’t. To this day, that ominous funnel cloud is the only one I’ve ever witnessed, and I harbor a healthy respect for bad weather. Sara spent weeks covering the aftermath of the storms and got several front page bylines in the Commercial Appeal. Her River Road ordeal was probably the most dangerous situation she ever got herself into, between the flooding car and the local loonies, and I just have to admire her courage and determination to get the story at whatever cost.